Is there a stranger film to win a major award at the Cannes Film Festival than “The Meaning of Life”? The final Monty Python feature film took home the Grand Prix at the 1983 edition of the festival, and looking back on it 40 years later, it's still apparent that the comedy troupe was still firing on all cylinders right to the end of their run.

“The Meaning of Life” feels like the Pythons returning to their roots. Its structure — consisting of loosely connected sketches in the same vein as their tv show “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” — is much looser than their previous two features, but this leads to the quality of the comedy on display being far more varied. This freedom is refreshing after “Life of Brian.” As great as that film is, the targets of the group's satire are restricted by the Biblical setting and themes. In “The Meaning of Life,” the Pythons can tackle religion, educational institutions, the military, corporate greed, and more because a narrative isn't holding them to one idea. This doesn't seem like it would make for a thematically coherent film, but it surprisingly does. Much like the search for the meaning of life, searching for meaning in this film is a futile endeavor. The meaning of both, as revealed at “The End Of The Film,” is not that deep.

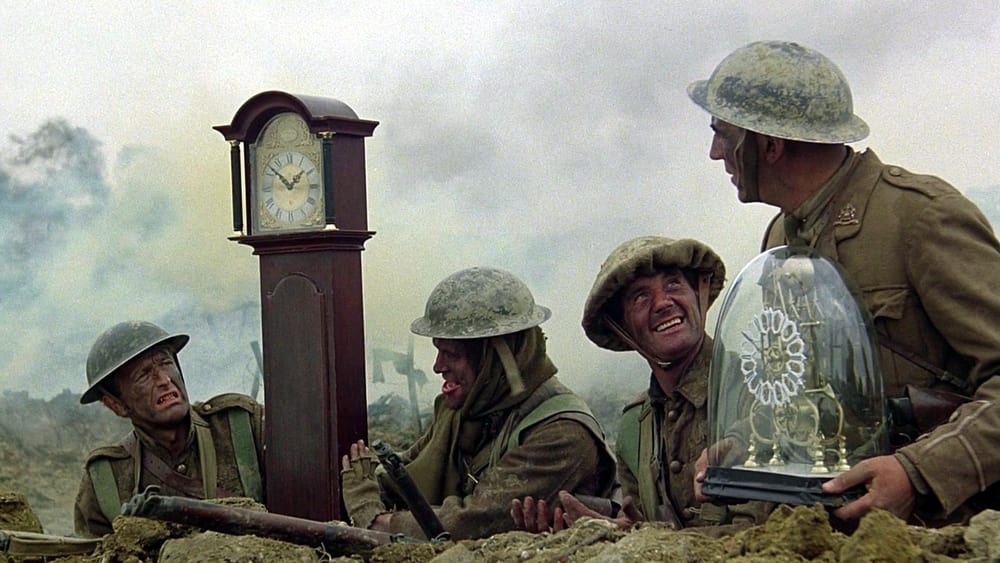

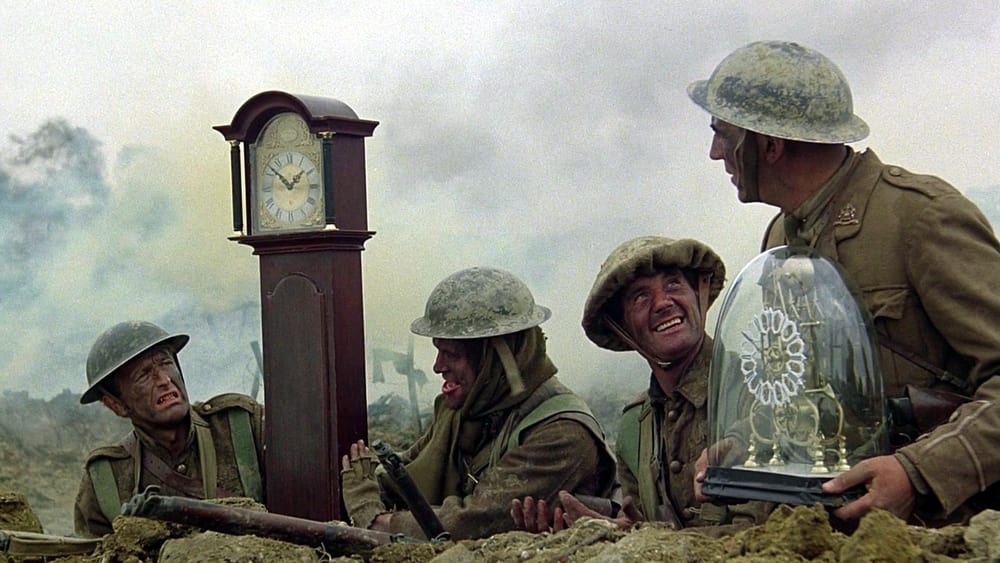

Because “The Meaning of Life” feels much more like “Flying Circus” than their previous two features, the best sketches make the most use of the vastly expanded budget and scope that film allows over television. The elaborately choreographed musical number “Every Sperm Is Sacred,” the harrowing World War I production design surrounding the trite arguments about gift-giving in “Fighting Each Other,” and the (what would probably have looked way better in 1983) computer effects sequence that accompanies “The Galaxy Song.”

Though not the funniest, the most visually audacious sketch of the bunch is the preceding short film “The Crimson Permanent Assurance,” in which a group of oppressed accountants become pirates, destroying and pillaging the highest institutions of global capitalism. Directed by Terry Gilliam, the sketch looks and feels like a warmup for his fantastic 1985 feature “Brazil.” The grand scope provided by the miniatures and set design is very reminiscent of Gilliam's next film, and even thematically — as much as a comedy short about elderly accountants/pirates can have themes — it feels complementary to “Brazil” in its lampooning of corporate culture.

Conversely, the worst sketches are often mere conversations, not using the larger-scale production values a film provides. The “Middle Age” segment, about an American couple on vacation in a restaurant that serves conversation topics, is dull in all aspects — from its jokes to its filmmaking. Thankfully, not many segments fall into this trap, but the ones that do are difficult to get through.

Though all of the Pythons are given their moment to shine, John Cleese emerges as the standout. Often playing absurdist characters, his dry, matter-of-fact delivery and sharp sense of timing means he can get laughs even when the joke isn’t funny. But when given great material, as he is in the “Sex Education” sketch where he plays a school headmaster teaching schoolboys about sex by demonstrating the act for them, it's a prime showcase of his immense comic talent.

Given my rabid Monty Python fandom in high school, I'm shocked that I had never seen “The Meaning of Life” until now. I'd seen a couple of the sketches and listened to all of the songs on the “Monty Python Sings” album, but seeing the film in full brought a new admiration for the project’s ambition. It may not be as consistently funny as “Holy Grail” or “Life of Brian,” but the best moments in “The Meaning of Life” are some of the best in the Python canon.