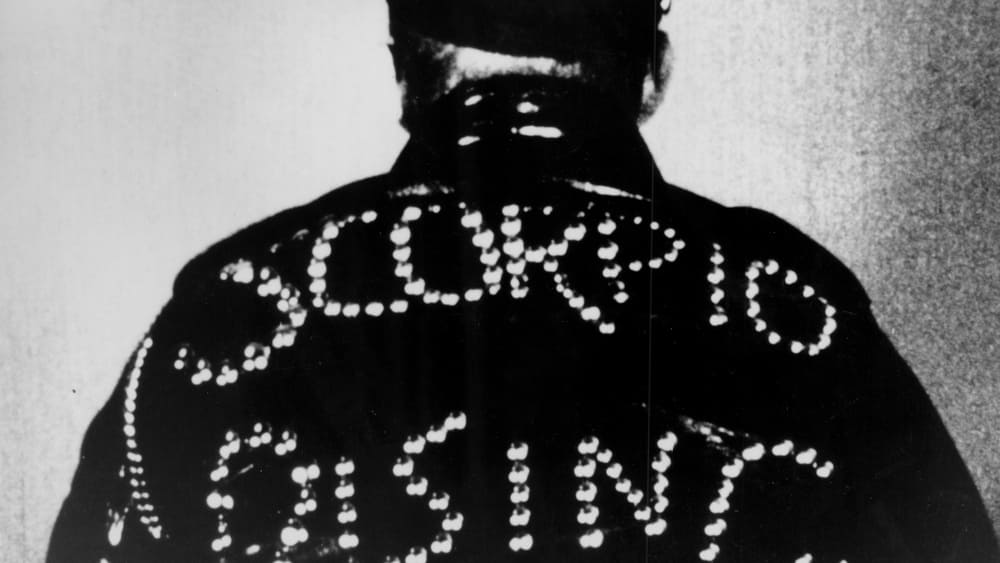

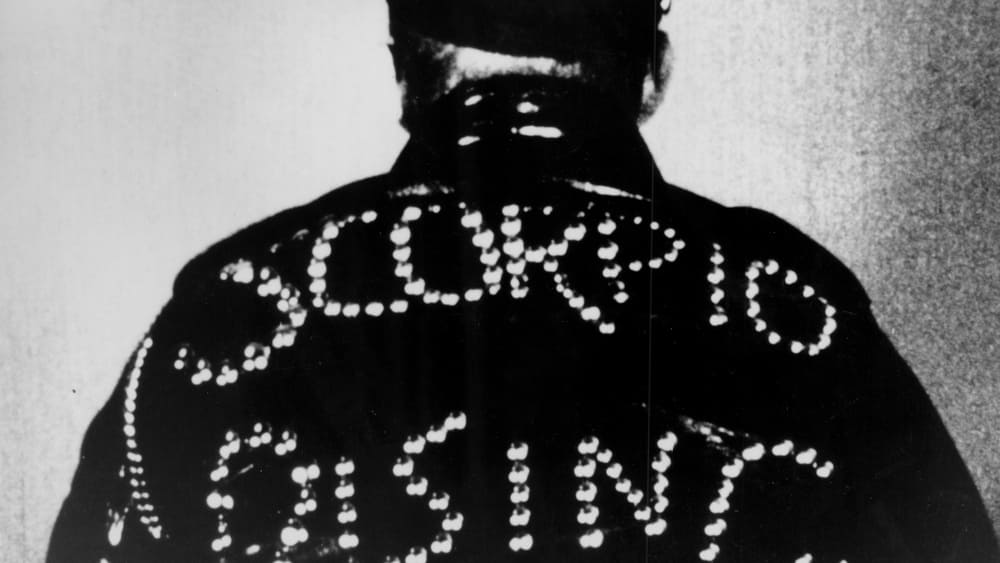

The great avant-garde filmmaker Kenneth Anger sadly passed away at 96 on Wednesday. As a tribute, I’ve decided to look back at one of my favorite films of all time, his 1963 experimental short “Scorpio Rising.”

Its largest influence on the medium is apparent almost immediately when Ricky Nelson’s “Fools Rush In” plays over shots of a biker fixing up his motorcycle. The constant use of pop music throughout the short is probably what it’s best known for, and the blueprint for using pop music to set a mood or get us into a character’s headspace can be seen in work by a wide variety of artists, from Martin Scorsese to James Gunn. The music isn’t used as mere window dressing as it is in many modern films and television shows. It adds energy to “Scorpio Rising,” from the opening images where the pacing is more pulled back — the imagery is not nearly as provocative as it will become, the shots are held longer, and the camera movement is slower — to the hectic, fatal finale set to The Safaris’ “Wipe Out.” But more than that, the film wants to use pop music to create a dissonance between what you hear and see.

The often upbeat music is constantly at odds with the images on screen. One sequence shows a young man, part of the group of bikers, grabbed by the others and stripped down before being covered in mustard. It appears this may be all in good fun — the young man is smiling during the ordeal with nothing violent happening to him. But the song that plays on the soundtrack is Kris Jensen’s “Torture.” Are we meant to take this as an implication that the young boy is being tortured, that something more sinister is happening? Or should we pay closer attention to the lyrics, which indicate the torture stems from being unable to love the person Jensen is singing to and act as the voice of these bikers whose homosexuality was only just becoming decriminalized in some parts of the country at the time of the film’s release? This ambiguity is part of the film’s power. It can mean many things to many people, and the more times it’s seen, the more interpretations it brings. The barrage of images and sounds comes so fast that the answers aren’t going to come right away. It demands repeat viewing, each successive watch making it a richer text.

Perhaps the film’s most terrifying and moving passage is accompanied by Little Peggy March’s “I Will Follow Him,” which splices together clips of one of the bikers standing above the rest as if he were a priest, Nazi iconography, and Jesus Christ. As the soundtrack blares “I love him!” and “Where he goes, I’ll follow,” Anger draws parallels between the cultlike worship of larger-than-life figures by people who are often lost and oppressed. Despite Jesus representing pure good and Adolf Hitler representing pure evil, the unwavering sense of devotion groups can feel towards any individual or ideology can only lead to death and destruction, just as it does for the bikers by the film’s end. Anger is also no doubt commenting on the persecution of LGBT+ people by Christian institutions, especially during that era in the United States. By intercutting images of Jesus with those of Nazis, Anger shows that we should not look at persecution differently based on who it's coming from or who is being targeted.

Today, “Scorpio Rising” is not just one of the greatest achievements of 1960s American avant-garde cinema. It remains one of the best films ever made. It's a transgressive work of art that is still provocative even after 60 years. Its influence is so far-reaching now that some artists unknowingly use techniques pioneered in this short. It perfectly represents the heights film as a medium can reach — a provocative deconstruction of space and time that creates a moving dissonance between the viewer’s visual and auditory senses.