-

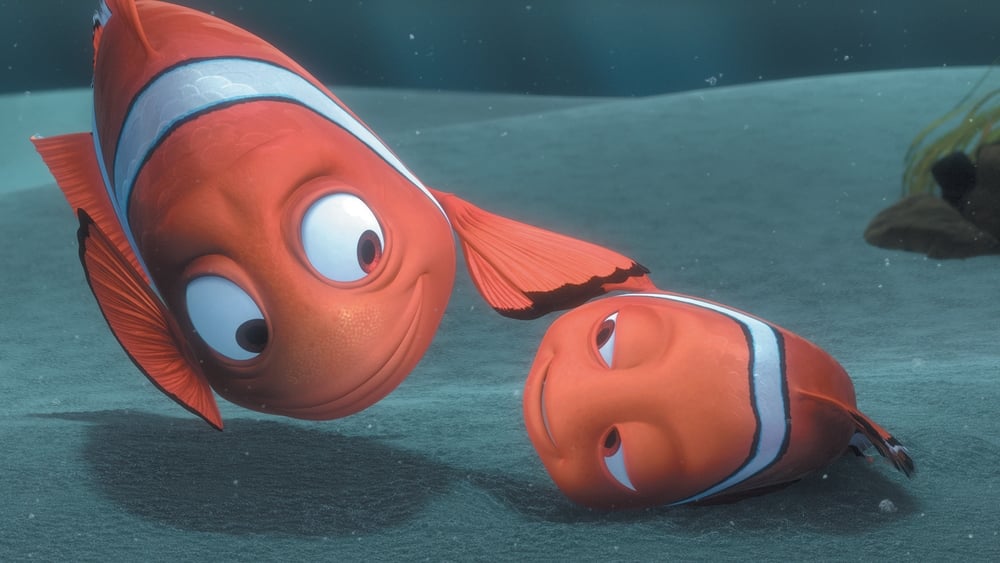

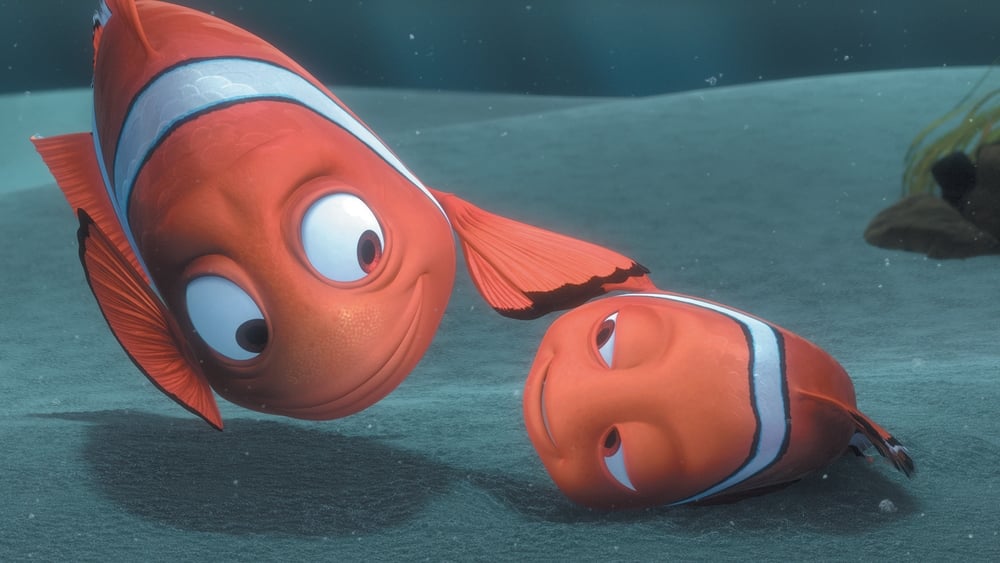

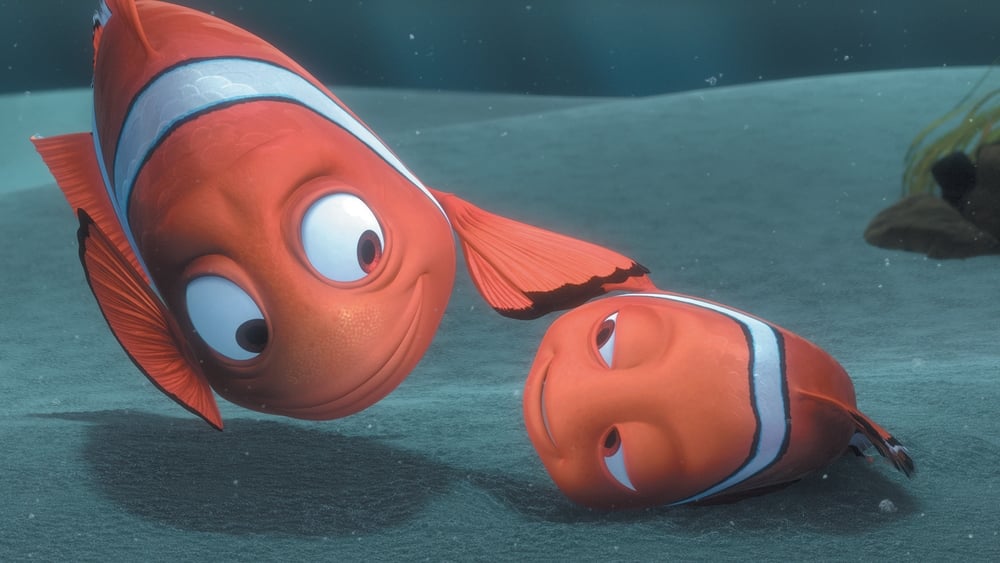

20 years later, 'Finding Nemo' is Pixar at its peak

by Mitchel Green - June 16, 2023

|

mitchelgreen34@gmail.com

source: The Movie Database

source: The Movie Database

After one of the most incredible hot streaks any studio has ever been on, Pixar has been slumping for more than a decade now. Since the release of “Toy Story 3,” a film met with huge commercial success and critical acclaim (it grossed over a billion dollars and became just the third animated feature to get a Best Picture nomination), Pixar has spent the last 13 years bouncing between unnecessary sequels and middling children’s entertainment. Occasionally a glimpse of the studio’s former greatness will reveal itself, as it did with “Soul” and “Inside Out,” but these great animated features are becoming the exception instead of the norm.

But what changed? One could point to Disney purchasing the company as the turning point, but that happened in 2006, with several hits still to be developed in the following years. Oddly enough, I think there’s a potential answer in the teaser trailer for “WALL-E,” in which director Andrew Stanton talks about a lunch a few critical artists at Pixar had in which they laid out ideas for future movies that ended with their 2008 masterpiece. That Pixar’s subsequent devolution into churning out more sequels than original films coincides with running out of the ideas batted around at that meal in the mid-90s is probably not a coincidence. Under Disney's management, there was no way they would allow Pixar artists to spend 10+ years developing ideas before making something that the corporation could profit from. But I think the answer to what happened to Pixar is far simpler — Pixar started making movies aimed at children instead of everybody.

You may not think there’s a difference between the two, or you may argue that Pixar always made movies aimed at children, but certain elements distinguish the two. The difference is that movies for everyone tend to treat viewers of all ages as equals. These films may be simple enough for children to understand but don’t shy away from more complex emotions and issues. “Up” can be both a fun adventure comedy for children and a devastating rumination on loss and grief for adults. Contrast this with something like “Cars 2,” a James Bond riff that has absolutely nothing of value in it for adults (or children for that matter, but that’s a whole other piece), throwing in several references to other properties adults are familiar with as a consolation instead of creating a film that can appeal emotionally to adults and children.

There’s a sense that Pixar has been playing it safe for some time now — the “what if [blank] had feelings” meme is true in the sense that Pixar has settled into a formula that it rarely breaks and seems to have created a model in which more time and energy is spent on what has feelings and not the emotions themselves. This is particularly worrying about the upcoming release “Elemental,” which, based on the marketing, seems way more focused on world-building than on its basic “people with differences can live in harmony” story (fully prepared to eat my words if it’s good). It all feels so surface level, fine for entertaining children, but not for viewers of all ages.

As someone in my 20s, I probably shouldn’t be responding to Pixar movies the way I did growing up, but those early films still have the power to move and entertain me. Nostalgia plays a factor, but I don’t feel the same way about several Disney/Dreamworks movies I enjoyed when I was younger. Revisiting those early Pixar films as an adult, I can look at them from different angles and appreciate new things about them. As a child, I loved the second half of “WALL-E” as a fun sci-fi adventure, but now I adore the first half on Earth which plays out like a post-apocalyptic Charlie Chaplin film. These Pixar classics are layered, not cheating the children or adults in the audience by treating one group as an afterthought.

There is so little variance in quality between the golden age Pixar films that deciding on a peak always comes down to personal preference. A credible argument could be made for eight or nine features as the studio’s best film. I don’t think Pixar has ever been able to top their 2003 feature “Finding Nemo.” There’s a bit of personal bias here. It was the first film I ever saw in theaters, although I quickly had to be taken out of it because I was so scared of the sharks. But it remains the Pixar film that packs the biggest emotional punch.

It’s weird that I gravitate toward films with complicated father-son relationships — as my love of Wes Anderson and Steven Spielberg movies shows — given my good relationship with my dad, but something about those kinds of films speaks to me. They dramatize deeply felt anxieties about potentially losing that wonderful relationship with my dad, and, by the end, the father and son still can at least come to an understanding of one another, even if their relationship isn’t perfect. I don’t want all movies to have a happy ending, and often these types of finales will get an eye roll from me, but in father-son films, the saccharine ending moves me almost every time.

The father-son relationship is not what I loved about “Finding Nemo” when I was younger. It was the breathtaking animation, how funny Dory was, and the exciting adventure. But as with all the Pixar classics, “Finding Nemo”’s layers reveal themselves to people at different stages in their lives. If I ever become a father myself, I’m sure I’ll have yet another new perspective on why the film is great. It’s certainly one I’ll be showing my future children over and over again.